My review of One Direction-Where We Are-The Concert Film appears here on the fabulous Talkhouse site where filmmakers review films and musicians review music.

Seeing “Finding Fela” a documentary film by Alex Gibney

Fela Kuti was born in 1938. By the time of his death in 1997, he was witness and agitator to the end of Western European colonialism and the rise of independence across Africa. If he had faults, one could call him a man of his times — sexist but loving women, tribal without a sense of community order, sexual to the point of self-destruction — but his supernatural bravery as channeled through lengthy booty-shaking trance jams approached a megalomaniacal dream utopia. The kind a shaman summons. He made music serve a higher god.

Listening on a subway into Manhattan, the music and insanity of a Fela show washes over me.

It’s around 1988 in Austin, Texas at the beloved club, Liberty Lunch. It seemed like there were 20 to 30 people on stage. (And how they traveled across the U.S., I’ll never get. Fela’s entourage even included a crew of women cooks who fed the band out of giant, steaming pots, scenting the entire evening with the simmering meat, beans and curry of a village meal.)

It’s around 1988 in Austin, Texas at the beloved club, Liberty Lunch. It seemed like there were 20 to 30 people on stage. (And how they traveled across the U.S., I’ll never get. Fela’s entourage even included a crew of women cooks who fed the band out of giant, steaming pots, scenting the entire evening with the simmering meat, beans and curry of a village meal.)

Here are some of Pat Blashill’s photos of the show here.

The dancers were spectacular, sexual, frightening. The horns and drums drove you to move for hours. And then there was the master calling you out of yourself and into a mass hypnosis that felt like the building would levitate. Stunning. Miraculous. A terrifying and magnificent vision of African pride and mastery that blew us all away. It put musical history in perspective and us, in our places.

It was with despair, that my pal Fadil described to me the next morning, how members of the band had asked him to find a crack dealer after the show. We couldn’t imagine such a spiritual experience resulting in a crack high. But that was Fela’s world. And while everything about that space/time dimension is gone — the club, the man, the kind of place Austin, Texas used to be — the spiritual and sonic resonances of the fiery energy of a live Fela show remains.

And after seeing Alex Gibney’s fine documentary, “Finding Fela”, the crack and spirit of a Fela show starts to make sense. Like an African Chogyam Trungpa, the quixotic “bad boy of Buddhism,” who brought Tibetan Buddhism to the U.S. drinking and fucking the whole way, Fela defies our sense of what a leader should be.

For a documentarian, culling through hundreds of hours of footage to decide what to include in a feature doc is often the most difficult challenge. This is especially true when the subject has the kind of contradictory reputation that Fela does. Making all the mechanics invisible so that the subject comes to life as if no effort went into it and the story flows forward, may be one of the most under-valued aspects of documentary filmmaking.

Reviewers often criticize portrait films if they don’t dig deep enough. But sometimes the subject is remote, unknowable. There are deep interior resources of a person that cannot be accessed by a camera. Some people refuse to be known. And with only archival footage to see the man himself, Fela seems to elude us even as we learn the facts.

From my own filmmaking experience, I understand how a subject can dodge and evade. But the film gives us quiet clues to Fela, the man — he treated his children as members of his ragtag commune and nothing more, he kept his home in Nigeria despite being jailed as a dissident, he was constantly unfaithful to his first wife (and the 27 that followed), and was hoodwinked by a spiritualist from Ghana, but he preached pride in his heritage as an African and demanded that African music be considered as seriously as Bach and Beethoven.

The documentary uses as its narrative spine, the development of “Fela!” the Broadway show created by dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones and Jim Lewis. Both film and musical conjure Fela’s flawed genius and describe a courageous life in which Nigeria was always worth fighting for.

In the film, Bill T. Jones describes the decision not to include Fela’s death by HIV in the musical. Himself, an AIDS survivor, he muses on the right or wrong of his artistic choice. (His longtime partner Arnie Zane died the year I saw that Austin Fela show. Years earlier, the Arnie Zane/Bill T. Jones Dance Company had come and taught a week-long dance intensive at my college and the thing that I will never forget is how no one really looked like a ‘dancer.’ They were all sizes and shapes. Arnie and Bill themselves so different – Arnie short and small and white and Bill, tall and elegant. Their love and work, a testament to changing opinions of what dance and art and sexuality could mean. The AIDS crisis was just beginning and we were all learning our friends were infected. We were 20 and my soon-to-be HIV+ friend Bob Ed and I sat in the dance intensive with Zane and Jones, wondering if we would ever be as marvelous as these creatures.)

So, if Jones doesn’t want to define Fela by his death and by default be defined by AIDS himself and chooses to cut this out of the musical, we are lucky that the documentary is a different artistic animal. The film describes the bravery it took for Fela’s family to come forward. And it is with these choices, that a documentary can shine or go dull. To understand the conflicted and contradictory nature of Fela, his family and a country in transition, the film explains the difficult choices that each took.

And joyfully, Fela’s music is what comes through loudly in the film. He declared it African Classical Music. (The jazz saxophonist Rahsaan Roland Kirk used the term Black Classical Music and this feels more aptly expansive.) But the idea of African Classical Music was one of Fela’s savvy detournemnts in his cultural fencing game with white, western hegemony.

In Adam Kahan’s excellent music documentary on Roland Rahsaan Kirk, “The Case of the Three-Sided Dream”, (as yet unreleased due to funding) we see how Kirk, like Fela, was engaged in the delicate swordplay where one’s culture is ransacked yet kept out of the serious music club. If only these two men had been in a room together with some instruments and a recording device — the music and talk and cosmic discussions that would have resulted…

In Fela’s case his fierceness informs Beyonce as much as Occupy Wall Street. While the sources are buried, African Classical Music has become the soundtrack of our lives. And “Finding Fela” returns our history to us by exploring the quixotic nature of Fela’s trickster rebelliousness.

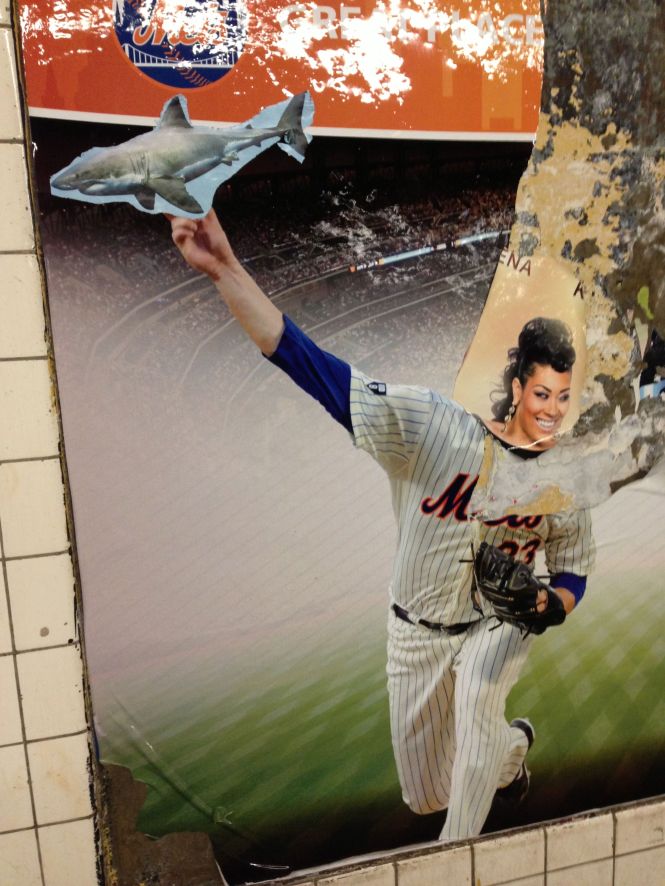

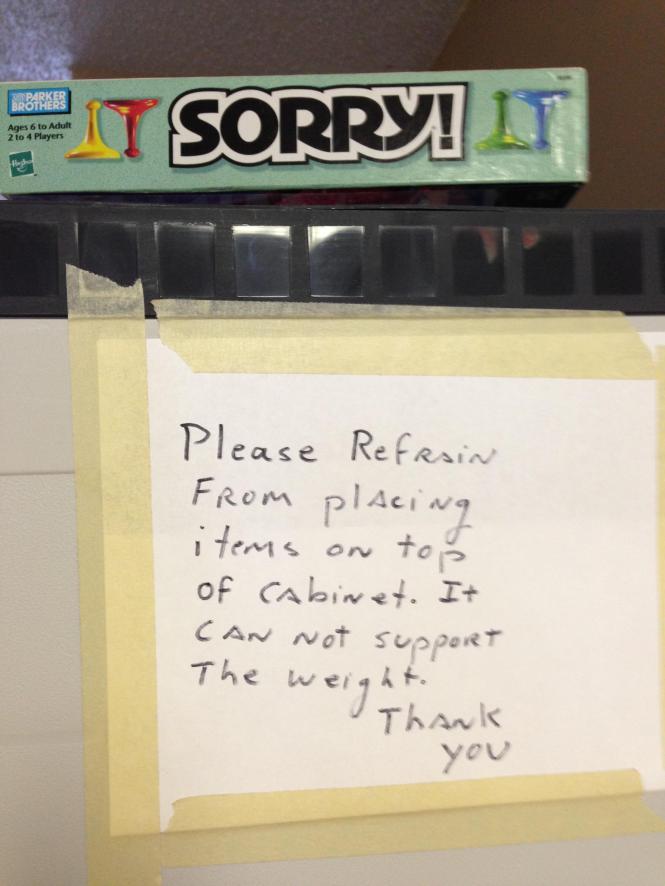

Weird dream…

Street Art Missive #11

“Who Took the Bomp? Le Tigre on Tour” screens in Brooklyn

“Look who’s here.

Well well well.

Guess it’s time.

For show and tell.”

Who Took the Bomp? Le Tigre on Tour

will screen at the Northside Film Festival at Union Docs

Kathleen Hanna and director Kerthy Fix in attendance for a post-film Q&A

UnionDocs Center for Documentary Art

322 UNION AVE.

WILLIAMSBURG, BROOKLYN, NY 11211